On March 16, 2016 I had the opportunity of participating in the Echo Parenting and Education Conference on Trauma-Sensitive Schools. It was the first international conference of its kind, attracting close to 300 participants. As we begin Child Abuse Awareness Month, I would like to share excerpts from my presentation.

On March 16, 2016 I had the opportunity of participating in the Echo Parenting and Education Conference on Trauma-Sensitive Schools. It was the first international conference of its kind, attracting close to 300 participants. As we begin Child Abuse Awareness Month, I would like to share excerpts from my presentation.

Trauma-Sensitive Schools: Teaming Up to Move Along

“What a wonderful event – a conference on childhood trauma for educators! I want you to know that there is so much to be hopeful about.

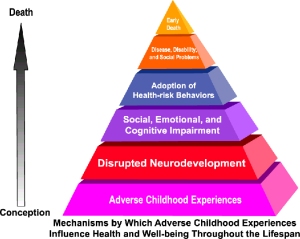

We now know that the brain’s neuroplasticity can be engaged to remedy or compensate for earlier adaptions to trauma that are no longer productive or beneficial. Brain based teaching and trauma-sensitive school experiences can help children move beyond trauma to embrace a future that includes academic and social mastery.

So what is the vision of a trauma-sensitive school? What makes trauma-sensitive schools so powerful in helping children move forward?

To be sure, they are inclusive school communities – no one needs to worry about not being good enough. They are communities characterized by what Carl Rogers referred to as unconditional positive regard.

One of the most devastating effects of childhood trauma is the paralyzing sense of isolation that accompanies it. Traumatized children are lonely children. They are alone in their shame, alone in their belief that they unlovable, alone in their efforts to contain very frightening feelings that cause them to behave in unpredictable ways. Trauma-sensitive schools embrace these children, and help build their capacity to connect with others.

Trauma-sensitive schools view children’s sometimes difficult behaviors as normal reactions to the adversity and trauma present in their lives. Staff don’t pathologize these behaviors but rather seek to understand them. I cannot emphasize this enough. Trauma-sensitive schools are not special placements.

They are neighborhood schools that follow the principles of universal curriculum design.

Using prevalence data, staff assume that a percentage of enrolled children have trauma histories. And they act accordingly. They build trauma-informed practices into everyday instructional routines throughout the school.

The trauma-sensitive framework does not subscribe to earlier paradigms for providing services to at risk children. Children do not need to be singled out to get what they need.

Rather, trauma-informed care is the norm. It is at the heart of the school’s philosophy, code of conduct, classroom behavior management.

A basic tenet of trauma-sensitive care is to avoid re-traumatization. We need to recognize that past efforts to address the needs of behaviorally disordered children have, in fact, been stigmatizing and sometimes coercive. We cannot afford to repeat these mistakes. Trauma-sensitive instruction cannot become a new category of special education provided only after an arduous identification process. It must be available to all children, all of the time.

That being said, trauma-sensitive schools do provide a flexible system of tiered interventions. Like PBIS, the first tier are universal supports that are sufficient to meet the emotional and cognitive needs of most children. But there may be days or weeks when these supports are not enough for some children to continue to succeed. More targeted interventions may be needed to help a child survive a crisis or other short-term problem. But I cannot stress enough the need for these interventions to be short-lived, and always with the goal of an eventual return to everyday activities and routines.

A new paradigm of professional development is needed to sustain this type of nurturing environment for traumatized children – one focuses on increasing staff awareness of the long-term disruption of cognitive, social, and emotional processes that may result from trauma exposure.

Educators cannot be expected to respond to children in a trauma-sensitive manner if they are not provided with state of the art training on how trauma effects neural development.

The goal is not to turn teachers into social workers or school psychologists. Rather, it is to give them the insights needed to prepare for occurrences of trauma related behaviors. Only then will they be able to respond in a manner that promotes resilience and rehabilitation.

The first priority is to integrate an awareness of the neurobiology of trauma into an educational framework. In particular, teachers need to understand the dynamics of traumatic re-enactment, and the effects of trauma on children’s regulatory systems.

Dynamics of Re-enactment

Teachers need to understand that children’s compulsive need for re-enactment jeopardizes teacher-student relationships. The drive toward re-enactment is like a rip tide that threatens to bring both child and teacher down. Here’s how it works. The child is always on the lookout for a parental figure, an authority figure to engage in his ongoing struggle to replay past traumatic experiences with him, with the hope they might have a different outcome.

Of course, none of this is conscious, but it is the basis for much of the provocative behavior demonstrated by traumatized children. Unless teachers are trained to recognize these behaviors as bids for re-enactment, they can get pulled into the undertow in one of two ways: by acting out of anger or by feeling victimized by the child’s rage. In either case, the child’s behavior will escalate and feel even more out of control.

Stress and Self-regulation

Teachers need to recognize trauma’s effect on children’s stress regulation. A whole host of behaviors ranging from low energy and lack of motivation to aggression and defiance, can be attributed to traumatized children’s inability to find and sustain a comfortable level of arousal. It’s the old “fight, flight, or freeze” problem. Children who “fight” in stressful situations become hyper aroused under stress. In a classroom environment they are likely to be defiant, noisy, and capable of prolonged acting out behavior. They are hard to manage and not much fun to have around.

Children who demonstrate “freeze or flee” behaviors downshift when their stress level becomes intolerable. They become hypo aroused, as indicated by their zoned out behavior. They appear unmotivated, disinterested, and may even fall asleep.

Now understand that we all have our own moments of “fight, flight, or freeze”. But these are quite different from the dysregulation experienced by children with early trauma histories. For one thing, ours are transitory – we know that “this too shall pass” and if we’re old enough, we even know ways of speeding up the process – taking a walk, calling a friend, taking a few deep breaths.

Not so for children with early trauma histories. Remember, trauma is the island where time stands still. Traumatized children see no way out. They can’t heal alone. They need our help.

Staff in trauma-sensitive schools know this, and with proper training, are able to engage children in a type of co-regulation similar to that observed in secure attachment relationships.

But here’s the rub. As Bessel van der Kolk and Bruce Perry so eloquently describe it, this is not a higher order thinking exercise. Rather, this co-regulatory relationship between teachers and students is sensory. Teachers in trauma-sensitive schools are trained to understand the physical nature of trauma. This knowledge enables them to integrate soothing, sensory activities into classroom instruction. Repeated often enough, these help children identify their internal state, and eventually, learn to control it.

We are talking about activities that have been understood as instructional best practices for years – things like movement, deep breathing, music, stretching, and frequent opportunities for self-reflection.

But integration of the sensory aspects of co-regulation into classroom instruction does appear to a place where trauma-sensitive schools break from their more traditional counterparts.

Certainly since the advent of “zero tolerance” policies, children are assumed to always be in control of their behavior, and it’s their choice to behave in defiant, self-destructive ways.

Nothing could be further from the truth in regard to children with early trauma histories. It’s not that they don’t know the difference between right and wrong. It’s that their behavior is reactive. They act before they think. They are stuck in survival mode, and can’t find a way out. And that’s where trauma-sensitive teaching comes in. It’s the means by which teachers and children working together create an exit ramp “.

To read more about the trauma-sensitive school movement, see Trauma-Sensitive Schools: Learning Communities Transforming Children’s Lives (2016). Available at Teachers College Press of http://www.amazon.com.

To learn more about Echo Parenting and Education, see www.echoparenting.org/who-we-are/contact–us

Please visit my blog at http://www.meltdownstomastery.wordpress.com

Instruction in trauma-sensitive schools honors the social nature of children’s developing brains. In this way, it is closely aligned with other educational best practices, particularly Carol Ann Tomlinson’s differentiated instruction, and Columbia’s workshop model. These designs emphasize collaboration, and group problem-solving. Both processes build children’s capacity for representational thought and perspective taking. These are critical elements of empathy and inferential comprehension.

Instruction in trauma-sensitive schools honors the social nature of children’s developing brains. In this way, it is closely aligned with other educational best practices, particularly Carol Ann Tomlinson’s differentiated instruction, and Columbia’s workshop model. These designs emphasize collaboration, and group problem-solving. Both processes build children’s capacity for representational thought and perspective taking. These are critical elements of empathy and inferential comprehension.

On March 16, 2016 I had the opportunity of participating in the Echo Parenting and Education Conference on Trauma-Sensitive Schools. It was the first international conference of its kind, attracting close to 300 participants. As we begin Child Abuse Awareness Month, I would like to share excerpts from my presentation.

On March 16, 2016 I had the opportunity of participating in the Echo Parenting and Education Conference on Trauma-Sensitive Schools. It was the first international conference of its kind, attracting close to 300 participants. As we begin Child Abuse Awareness Month, I would like to share excerpts from my presentation. No one questions that health care costs in the United States are out of control. Excessive drug prices, unnecessary medical procedures, and continued reliance on an outdated fee for service treatment model, are frequently discussed reasons for this economic dilemma. Childhood trauma and household dysfunction are seldom cited as possible factors. This oversight limits any viable solution to the problem.

No one questions that health care costs in the United States are out of control. Excessive drug prices, unnecessary medical procedures, and continued reliance on an outdated fee for service treatment model, are frequently discussed reasons for this economic dilemma. Childhood trauma and household dysfunction are seldom cited as possible factors. This oversight limits any viable solution to the problem.